AdvancedResearch

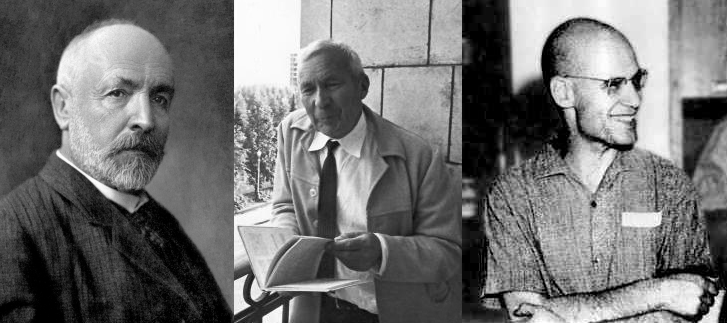

Cantor, Kolmogorov & Grothendieck

Georg Cantor created set theory and defined cardinal numbers.

Andrey Kolmogorov contributed to intuitionistic logic and defined randomness using undecidability.

Alexander Grothendieck created modern algebraic geometry and defined the homotopy hypothesis.

What if the work of these 3 people can be brought together into a single idea?

In Pocket-Prover, I am experimenting with a new logic, called Path Semantical Quantum Propositional Logic (PSQ), that functions very differently from Path Semantical Classical Propositional Logic (PSL).

PSQ and PSL are part of a family of logical languages that extends classical or intuitionistic logic with some notion of Path Semantical Quality.

Path Semantical Quality is required to make the core axiom of path semantics work. The core axiom of path semantics is believed to encode mathematics as a whole in a nutshell, by posing a problem of expressivity which solution yields a mathematical language (usually very low level).

The general idea of this problem is that there is no partial equivalence relation in ordinary classical or intuitionistic logic, so it must be added some way. It turns out there are several ways to do this, of which PSQ hints at something intriguing about the work of Cantor, Kolmogorov & Grothendieck.

A Brief Introduction to PSQ

PSQ adds a qubit operator which is equivalent to adding quality.

It is through the interpretation of qubit that one sees through a keyhole into the universe(s) of ideas by Cantor, Kolmogorov & Grothendieck.

First, a bit about how the qubit operator works.

It takes a proposition as argument and produces a new proposition which is “projected” randomly onto any other proposition.

This might seem intuitive, but one can think about it as introducing a new proposition depending on an existing proposition.

The only property

that the qubit operator needs to satisfy, besides being random and depending on the argument, is the following:

qubit(¬a) == ¬qubit(a)

The kind of randomness required is special, due to the value of a qubit needs to be frozen for each case, but vary across cases to produce correct results.

Since a qubit is random, there are some new theorems that are probabilistic and some new theorems that are deterministic. The new theorems that are deterministic are those who exploits the alignment of qubits. For probabilistic theorems, one can increase confidence in the result using repeated measurements.

The name “qubit” comes from the similarity to Quantum Logic.

Where Cantor Enters the Scene

Each proposition in Pocket-Prover might be throught of having a singular frequency. The singular frequency is the result of analysing the Fourier transform of the bit patterns. A Fourier transform in general might have multiple frequencies.

At first sight, these single frequencies seems neither to have anything concretely with theorem proving, nor with the work of Cantor. This is because the order of evaluating the cases, which affects the frequencies, does not matter for the truth value of the proof.

However, one reason these singular frequencies matters is because they are relative to each other. In order to verify a proof using brute force, one must necessarily check ever case in a such way that the relative singular frequencies are covered.

This is such a deep and profound idea, that I do not know how to express it formally.

Furthermore, once the idea of relative singular frequencies have been established, it is relatively easy to spot the one-to-one correspondence with natural numbers.

The qubit operator might be thought of as taking a natural number and “projecting” it into a similar space of natural numbers

where the order is broken. This broken order changes case by case, such that the entire space might be thought of as having

a higher cardinality than natural numbers.

With other words, the qubit operator allows “peeking into” the universe(s) of ideas of Cantor.

Where Kolmogorov Enters the Scene

Kolmogorov had the idea that a random string of symbols could be defined by the non-existence of some deterministic computer program below some fixed length of source code, that could reproduce the string. This is closely related to the idea of Kolmorogov Complexity.

However, the qubit operator shines a new light on Kolmogorov Complexity.

Instead of thinking of the complexity of some object,

one can think about the complexity of entire spaces of objects.

A space of objects can have relative complexity to another space of objects.

For example, natural numbers are isomorphic to any infinite discrete space.

Another example: Turing machines can simulate each other.

This means that the relative complexity of spaces has mathematical relations.

When these mathematical relations are analysed,

it turns out that the qubit operator can not be reproduced using any ordinary logic operator.

Remember that a random string can not be produced by any deterministic computer programs of a certain size. What if instead of a random string, one obtains something more deep and profound?

This is exactly what the qubit operator does: It is random in some sense, yes, but it is also more interesting than just pure randomness.

What makes the qubit operator interesting is that it depends on the argument.

So, in some sense, one constructs an “object” which is not constructible in any other way.

Where Grothendieck Enters the Scene

This is the stuff I know the least about, so I will keep it brief:

Grothendieck thought about a way to simplify the language of topology. This idea was formulated as The Homotopy Hypothesis.

The qubit operator could be how one can reason about topology within logic,

without needing the full language of geometry, which is the standard way of visualising topology.