AdvancedResearch

Levenshtein Heuristic in Poi

by Sven Nilsen, 2020

Poi 0.18 is released!

In this blog post I will discuss the new Levenshtein heuristic used in Poi.

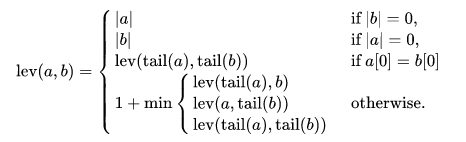

The Levenshtein distance measures minimum single-character changes between two strings.

It is named after Vladimir Levenshtein, which considered this distance in 1965 (Source: Wikipedia)

Why automated theorem proving is hard

Automated theorem proving is hard for the same reason the boardgame chess is hard.

The Shannon number is a conservative lower bound of the game-tree complexity of chess: 10^120. This is more than the number of atoms in the observable universe.

However, in automated theorem proving, the complexity is sometimes countable infinity. With other words, if one tries to search the whole space of possible proofs, the program will run forever.

Heuristic measurements

In order to prioritize search of possible proofs, one needs a heuristic.

Here, the word “heuristic” means the same as e.g. using utility to optimize course of action for AI agents. In fact, an automated theorem prover is very much alike an AI agent, except there are no interactions with an environment. The automated theorem prover usually lives in a world with “perfect information”, aka chess. However, there is no opponent. Instead, the “opponent” is the complexity of math itself.

The following properties was desirable when choosing a heuristic measurement for Poi:

- Reaches minimum value when reaching goal

- Smooth gradient when getting closer to the goal

- Rule agnostic

- Easy to maintain

My first idea of how this heuristic should look like, was something that used sub-expressions matching with the goal.

I was thinking about how difficult this would be to code.

Then, I realized that I was thinking too complicated: Why not use strings instead of expressions?

Levenshtein distance

The Levenshtein distance is the minimum number of single-character edits required to transform one string into another string.

For example:

lev("a + b", "c + d") = 2

This is because you only need to replace a with c and b with d in the first string to get the second string.

The Levenshtein distance also allows adding and removing characters, but not swapping them.

At first sight, it might seem a bit hacky to use strings this way, when we are talking about a theorem prover which uses complex expressions behind the scenes.

However: It satisfies all the properties I mentioned above!

For example, an alternative could be to use machine learning, which would become gradually better at assisting the theorem prover over time. In this case, you would probably use strings, bytes or numbers to feed the neural network. Would you consider this to be a hacky solution too?

I am interested in hearing what people think about what they consider a hacky heuristic versus a more robust heuristic.

So, why not just use a simple string algorithm? After thinking about this, I decided to go for it, because I could not figure out any rational reason to not do it.

Try first, learn afterwards

How did I figure out whether Levenshtein distance was the right heuristic to use?

I simply added levenshtein to the Cargo.toml and coded for a few hours: Turned out that it works pretty well.

It took a couple iterations to get it right. At first, the algorithm just picked the minimum Levenshtein distance from unreduced equivalences. This worked surprisingly well, but more testing revealed that this algorithm was not sound.

I ended up with using std::collections::{BinaryHeap, HashSet} instead,

picking the minimum Levenshtein distance across all sub-proofs found so far.

This algorithm fixes the soundness problem, but uses a lot of memory.

Only after getting it working, I learned more about the theory behind Levenshtein distance in detail.

Thoughts about the design

Since Levenshtein is not very good at strings where substrings are swapped, I believe it will perform less well on commutative operators.

However, I believe that using the normal exhaustive search up to some depth, will resolve some of the issues with commutativity.

The problem is how to deal with large expressions and lots of commutative operators, e.g. addition. In this case, increasing the depth of exhaustive search will lead to significant slowdown.

One approach to solving this problem, is to assist the automated theorem prover by designing proper utility rules.

This is something I am testing now, by designing worst-case proofs and doing some experiments.

Utility rules

Utility rules are rules that can be proved from existing rules, e.g.:

x0 + x1 + x2 + x3 <=> x0 + x3 + x2 + x1;

The expression x0 + x1 + x2 + x3 is constructed similarly to a linked list (sort of).

The left-most term x0 functions as a “tail” that pattern matches anywhere in the expression.

Keeping the left-most term fixed on both sides makes it possible to manipulate the expression at any depth,

instead of manipulating only at the leafs.

This is important when there are long chains of commutative operators, because it avoids transformations via tree-like structures, which requires many more steps.

Although you can in principle prove the same using a + b <=> b + a only,

the automated theorem prover can not look that many steps ahead to make a realistic estimate using the Levenshtein distance.

Future improvements

In one test run I am running while writing this blog post, Poi uses 500 MiB of memory.

I might replace HashSet with a Cuckoo filter (an improved Bloom filter) in the future,

in order to lower memory usage.

Also, I would like a replacement for BinaryHeap which uses less memory.

Thinking a bit about Trie or finite state machines, as in the fst crate.

The problem is, I need to pop the minimum sorted by some numeric key.

Basically, I want something behaving like BinaryHeap, but more efficient for strings.

A minor improvement in performance could be to reuse the cache used in the Levenshtein algorithm.

At this stage, I am mostly focusing on testing that things work, but in the future I might be focusing to how long time it takes to complete the proof search. I have not decided yet whether the REPL should have built-in benchmarks or whether the REPL code should be refactored for running external benchmarks.